This graphic speaks for itself:

I’ve seen it on many sites, but no one seems to have the original attribution. If you know who created it, please share. And then, keep writing.

This graphic speaks for itself:

I’ve seen it on many sites, but no one seems to have the original attribution. If you know who created it, please share. And then, keep writing.

As in, lessons in writing, quite literally. Not typing. Not printing. Writing. If you’re using that artifact of yore, the fountain pen, how do you know the proper way to hold it, the proper way to angle it on the page, the proper pressure to apply, lest you unknowingly ruin the nib — and are thus forced to revert to less glamorous/capricious means of self-expression? I happen to write most of my fiction longhand–with a fountain pen, no less. The question for me was more than academic when I first held the alien instrument.

I was happy to discover that I wasn’t the first, and that my concern was in no way a product of the modern age of paperless communication. Here, a primer from A new booke, containing all sorts of hands (1611), from the Folger Shakespeare Library:

And here, a modern version, courtesy of Montblanc, which I have to admit is much like the original, if a touch less poetic:

I think I’m more impressed by 1611. “How you ought to hold your penne.” Good, naught. How can you not love it?

Images from The Collation’s “Spotlight on a Calligrapher” and the Montblanc website “product care” section.

As I struggle to finish the first draft of my manuscript, I find this strangely inspiring and comforting:

It’s the first page of Vladimir Nabokov’s first draft of Invitation to a Beheading, or, in its Russian incarnation (pictured here), Приглашение на Казнь. As I look at it, I’m reminded of Mark Twain’s words, “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—’tis the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.” It’s easy to forget that hardly ever do we get to the lightning without a struggle.

Many thanks to Jonathan Gottschall for providing the image–and more inspiring first drafts on his blog, here.

And now, onwards with the writing.

A thank you to sure-eyed reader JSM for tracking down and providing the accurate version of the Mark Twain quote.

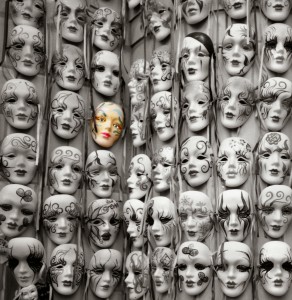

Today, I discovered a new word: Maskenfreiheit, the freedom conferred by masks. Apparently, John Updike was a fan, relishing the ability to obtain some semblance of anonymity by hiding behind his characters: you can’t be blamed for the actions of a character you’ve created. True enough – though in the case of the writer, I suspect it’s not entirely true. Who can help but read autobiographical detail into even the most removed creation? And who, knowing the writer, can resist the egotistical impulse to take personally something that was likely not meant for him (though, of course, it might have been–and that ambiguity invites even further speculation)?

Today, I discovered a new word: Maskenfreiheit, the freedom conferred by masks. Apparently, John Updike was a fan, relishing the ability to obtain some semblance of anonymity by hiding behind his characters: you can’t be blamed for the actions of a character you’ve created. True enough – though in the case of the writer, I suspect it’s not entirely true. Who can help but read autobiographical detail into even the most removed creation? And who, knowing the writer, can resist the egotistical impulse to take personally something that was likely not meant for him (though, of course, it might have been–and that ambiguity invites even further speculation)?

Writers aside, I think Maskenfreiheit speaks to an incredibly powerful phenomenon that has long captivated me — and frightened me to no end. Up until now, I just didn’t realize there was a word to describe it. Maskenfreiheit captures why I am so afraid of carnivals, of masked balls (not that I am invited to many), of clowns. When you, in effect, erase your face, you erase some inner sense of responsibility. You can try on actions that the real-life you would never dare. You can become the owner of any face you choose. (And, of course, there’s the flip side: you can shed any face you choose.) Masks can be liberating, an opening to experimentation you would feel too self-conscious or constrained to attempt otherwise. They can have a dark side, an invitation to indulge your inner Mr. Hyde, so to speak. And even if at first, your Hyde isn’t all that evil, repeat experimentation may prove intoxicating. Masks can be addictive.

There is an eeriness to the mask, to the face that you can’t decipher or discern. An emptiness.

The perception of anonymity does strange things to people. It’s why so many websites ban anonymous commenting: if you don’t have to add a name to an opinion, you are free to endorse those opinions your “real” self would shy away from. You can be mean or spiteful or arrogant or whatever else you choose. Of course, there is the counter argument of freedom: you can say things you would otherwise be too afraid to express for fear of personal repercussions. Online or off, masks are the ultimate liberation and temptation, all in one.

And in that way, masks can actually reveal us as we really are more so than almost anything else. How do we behave when we are freed of social constraints? When we shed the responsibility of name and face and blend into the anonymous, the crowd, the faceless masses? How do we use our Maskenfreiheit? A thought exercise: what would you do, say, create if you knew with complete certainty it would never come back to you?

I can’t help but quote Sherlock Holmes here. His words are too à propos:

The pressure of public opinion can do in the town what the law cannot accomplish. There is no lane so vile that the scream of a tortured child, or the thud of a drunkard’s blow, does not beget sympathy and indignation among the neighbours, and then the whole machinery of justice is ever so close that a word of complaint can set it going, and there is but a step between the crime and the dock. But look at those lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.

Holmes will take the lowest and viles alleys of London over the smiling and beautiful countryside any day. And I have to say, I can’t help but agree with the sentiment.

***

Can a writer ever be anonymous? How much Maskenfreiheit can he ever really have? In some ways, writing is the least anonymous thing you can do. The more you hide, the more you reveal. Every choice says something. Even the pseudonym. It reminds me of Nabokov’s Pale Fire: layer upon layer of identity, until you’re not quite sure what is what. That old clichéd image of the peeling onion—only you don’t know which layer you’re holding and if it’s even an onion to begin with.

Writing is a mask, it’s true. But it seems to me a deceptive one. An illusion of anonymity. Then again–perhaps that is why it is, in the end, the perfect mask. As writers, we reveal, we hide, we dissemble, we direct, we clarify, we entangle. And ultimately, who’s to say what is really what, where one finishes and another begins? Apart from the guesses, what remains?

Image credit: Brian Snelson, Creative Commons.

Last night, I gave a talk at Housing Works Bookstore, as part of Geek Week and the Adult Ed useless lecture series, on what Sherlock Holmes has taught me about psychology. Thanks to everyone who was able to make it! Unfortunately, the talk wasn’t recorded, but I’ll work on recreating it in some form or other in the coming weeks.

I did include this clip from the first season of the BBC’s wonderful Sherlock. With luck, the audio will work better here than it did at the actual talk…

I hope you enjoy! And a big thank you to Jim Hanas for including me in the evening, along with such wonderfully talented people as Ben Lillie, Patrick DiJusto, and Cody Pope (and, of course, our host, Charles Star).

This is what today feels like. Now, I just need a way to swim out of there and get back to writing. Some days are just like that.

It reminds me of something I wrote a while back, on the key to making achievement out of procrastination: structured procrastination. Except sometimes, it doesn’t quite work out as planned.

I’m thrilled to welcome you to my new website. It has been many months in the making (thank you, Amy and Ethan! and thank you, Cara, for the phenomenal illustrations) and I couldn’t be happier with how it has turned out. I will be writing a proper introductory post later, but for now, I just want to say welcome, thank you for visiting, please look around, and please share any comments you might have.

Until soon.